diana lam

Predicting Yelp's Elite

As I mentioned in my previous post, I’ve been working on a project to classify the elite status of Yelp users. If you’re unfamiliar with what it means to be an “elite” user, you might want to read my previous post for a brief primer!

The goal

I’ve always been fascinated by how massive of a role Yelp has come to play in our day-to-day lives, and most of all, why and how users become “elite.” The goal for this project was to try and pin down some of the key factors for determining eliteness. Beyond my personal curiosity on the subject, this project could have two main applications:

- Help a Yelp user who wants to be elite get feedback on his chances; and

- Help Yelp as a company better choose whom to give elite status.

The approach and data

The data comes from the Yelp Dataset Challenge and covers user, business, review, and tips data for 10 cities across four countries. I wound up utilizing data for over 550,000 users, 2.2 million reviews, and 590,000 tip from this set.

Since I was focused on both Yelp users and Yelp as a company, I wanted to emphasize both model interpretability (for the Yelp user) and model performance (for Yelp as a company). I tried a range of classification models, including linear classifiers (logistic regression and linear SVM) with stochastic gradient descent optimization (since my dataset was so large), naive bayes, and random forest classifiers, but ultimately would up settling on random forest, which satisfied my desire for performance and interpretability (more on that below!),

Models were evaluated using five-fold cross-validation for a range of scores, including accuracy, precision, recall, f1, and AUC. I also used grid search to refine the hyperparameters for my final model.

The analysis / feature design

I focused my investigation on four categories of user characteristics, based loosely off the “authenticity, contribution, and community” criteria publicized by Yelp. They were:

Activity: Very simply, the amount of content a user generates on Yelp. This includes number of reviews and number of tips written.

Popularity: The size of a user’s social network in terms of friends and fans and the votes/compliments they’ve received on their profile and review content. Votes and compliments are the Yelp equivalent of likes; votes are anonymous, can only be given on reviews, and are categorized as “useful”, “funny”, or “cool.” Compliments are anonymous and can be given on a review or just simply a profile, and have far more categories, ranging from things like “hot” to “profile” to “photos.”

Review sentiment/content: Average star ratings given by the user, whether or not the user’s reviews mentioned price, and the most common words used by elite vs. non-elite users. I did my own, simpler version of weighting (a la tf-idf) and topic modeling to dissect content.

Review structure: This metric captures the user’s review style–length of review in terms of number of paragraphs and sentences, average words per sentence, characters per word, use of all caps, and use of exclamation marks.

Although I was most interested in seeing how the content and style of the user’s reviews would impact their elite status, I had a hunch that the prediction would be driven by their activity and popularity. So how did the results pan out?

The findings

My final model had an accuracy of 98%, f1 score of 80%, and AUC of 99%. Compared to an accuracy and AUC of 94% in the baseline model (where one would predict the most commonly occurring class, non-elite, every time), my model was able to account for about 70-80% of the missed accuracy and AUC points of the baseline.

I’m pretty happy with the performance, especially since my model was able to overcome the significant class imbalance present in the dataset without needing to over or undersample.

What’s most fascinating is the actual importance of each feature category, so let’s get into that!

Popularity

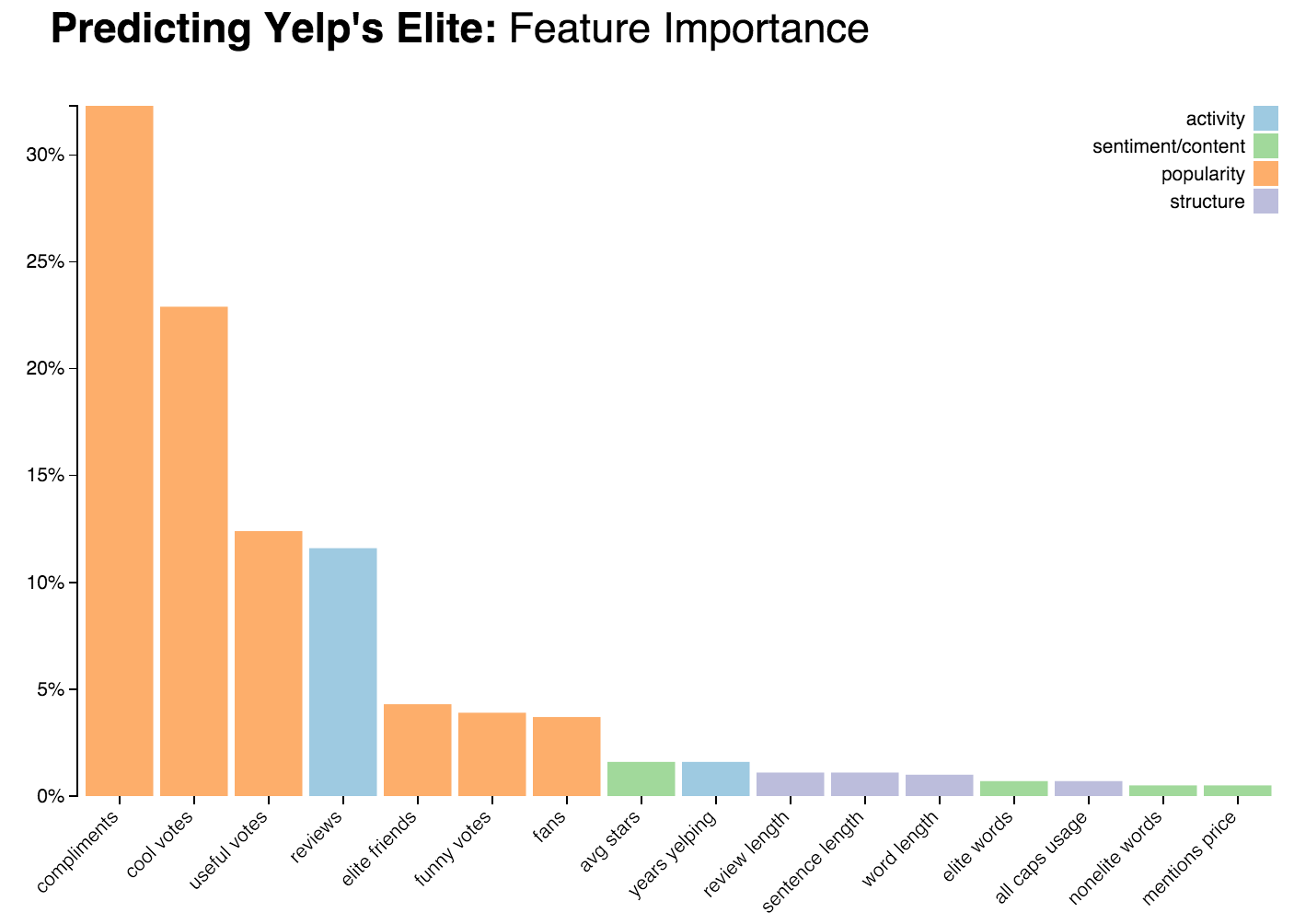

As we can see in the chart above of features and their relative importance in the final model, my hunch was correct–a user’s popularity was most important in determining his elite status. Popularity is a pretty broad category that encompasses two key features–1) the sheer size of your social network, in terms of friends and fans, and 2) the amount of recognition a user reviews on their content through votes and compliments.

The latter category is most important, with compliments, “useful” and “cool” votes increasing a user’s chances of becoming elite. Interestingly enough, “funny” votes actually look away from a user’s chances at being elite; perhaps this is because things labeled as “funny” are more likely to be ironic/jokes/spam/bots and less useful?

On social network, the number of elite friends you have is far more important in determining elite status than the number of friends in general. On average, 70% of an elite user’s friends are other elite users, whereas only 24% of a non-elite user’s friends are elite users.

You can see the distribution of elite vs. non-elite users, their friends, and friendships in the network graph below. Elite users are in red and non-elite users are in grey. Each node represents a user and the size of the node is scaled to the number of friends that they have. Each line (or edge) represents a friendship. The graph only represents a small subset of users, but shows the nature of friendships across the entire dataset.

Activity

Number of reviews was the fourth most important feature, while years yelping was less important. Although we can imagine that the two are somewhat correlated–the more years you’re Yelping, the more reviews you have (assuming you’re a consistent Yelp user), a longtime user with few reviews won’t make the cut.

Another interesting thing to note here is that number of reviews is likely correlated with number of compliments and votes–the more reviews a user has, the more likely people will see their reviews, and the greater chances people will vote on them. At the same time, there’s only so much that volume can push a user’s popularity–if you have lots of reviews, but they’re all unreadable or have boring/useless content, you probably won’t get many votes or compliments.

Review sentiment/content

On average, elite users left slightly more positive ratings (3.8 average rating by elite users vs. 3.7 by non-elites) than non-elite users.

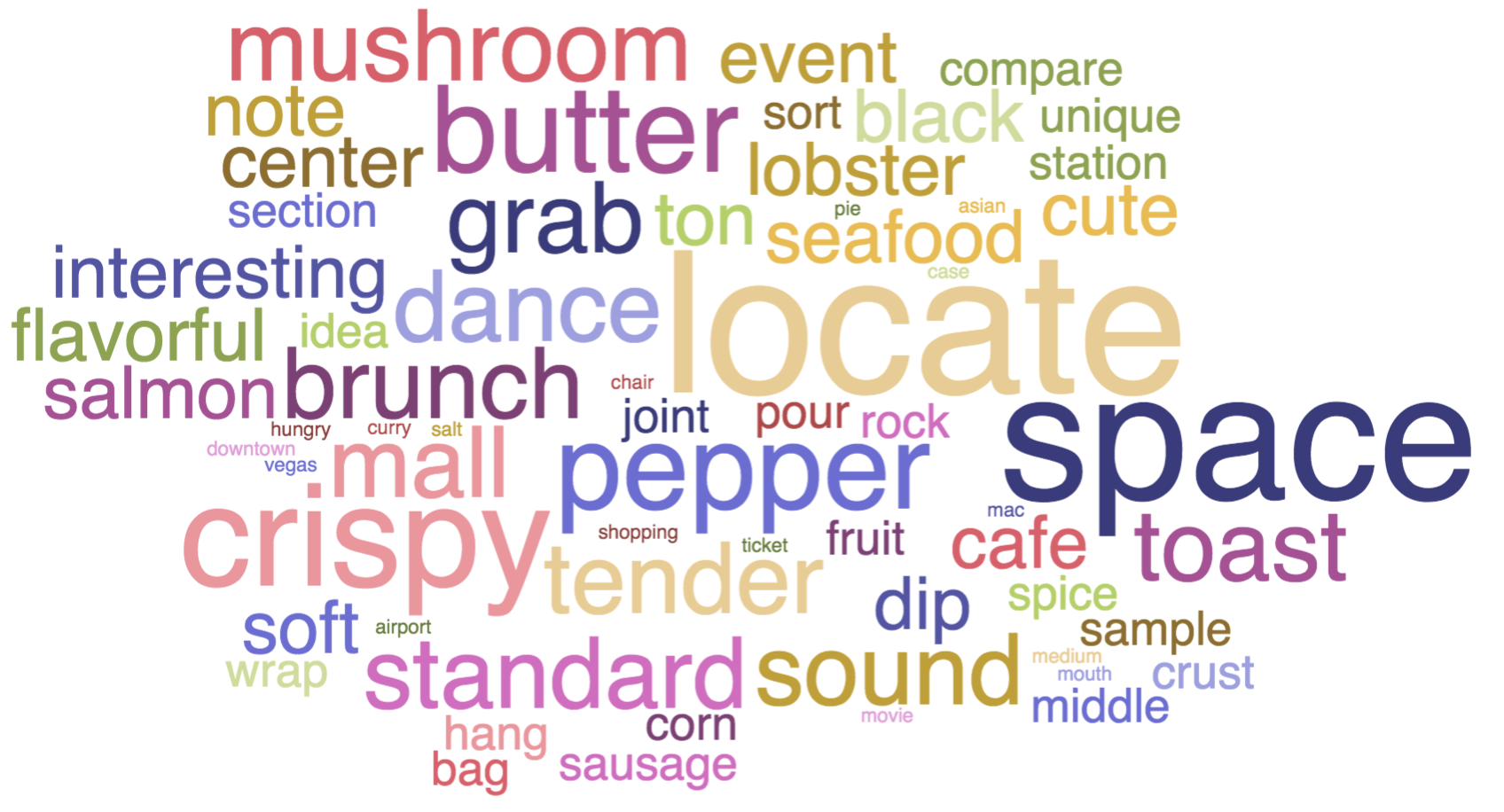

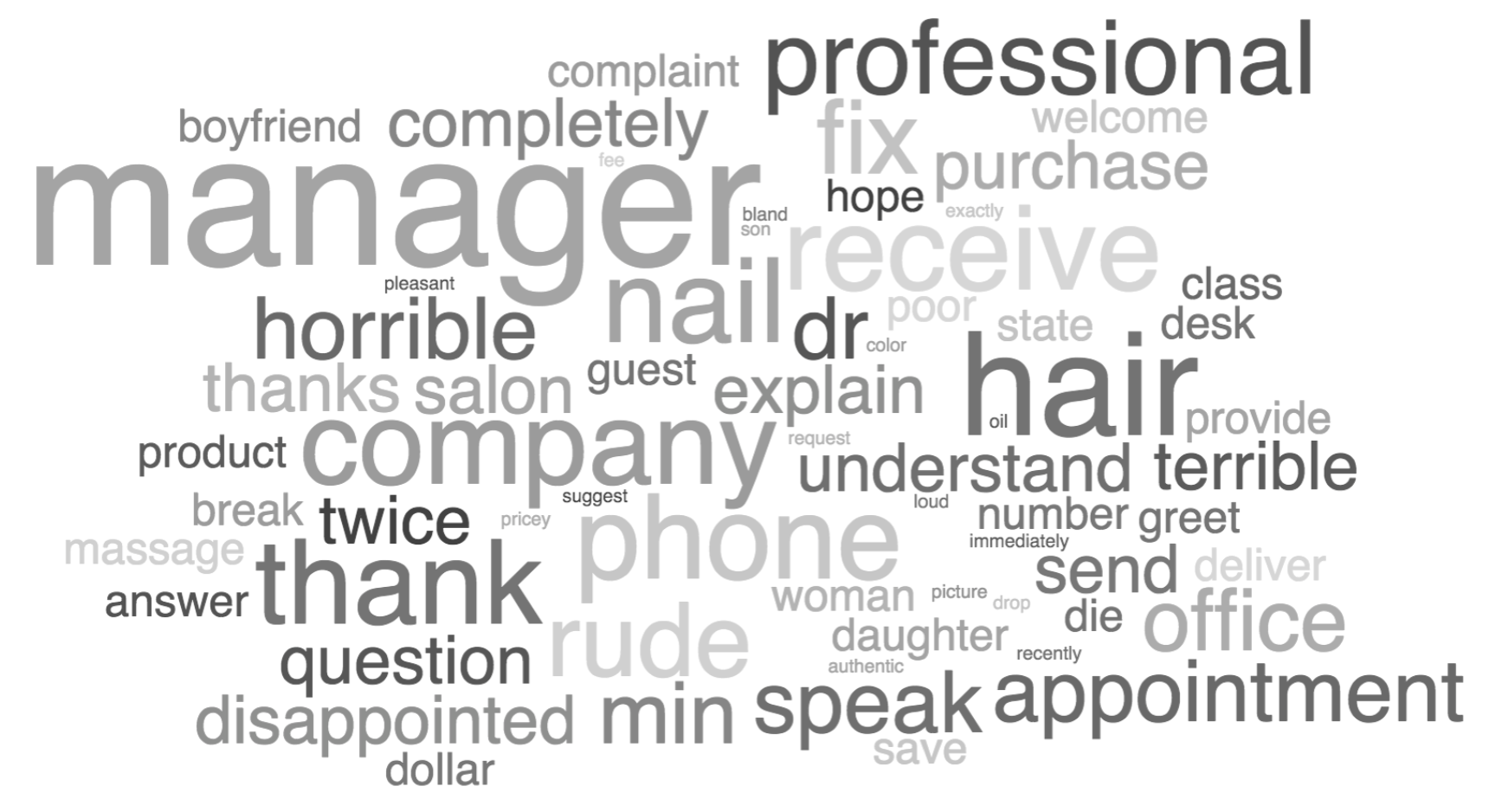

What’s really fascinating here is the content of reviews in elite vs. non-elite users; as we can see in the word cloud visualizations below (couldn’t help it!), elite users write more descriptively about the physical attributes of the business and the food. In contrast, non-elite users use more complaint type words and discuss elements such as service. Here, the content analysis reinforces the sentiment analysis of the star ratings.

Top 50 unique words used by elite users

Top 50 unique words used by non-elite users

Review structure

Review structure had the least importance here, but still contributed positively to the performance of the model. As expected, elite users wrote longer reviews that were structured into multiple paragraphs and that contained longer sentences.

Next steps

First - As I mentioned above, I was happy with the model performance of 98% accuracy. I would say it’s pretty rare that a model performs this well. When it does, it brings up the question of how classes are actually assigned. For such a high accuracy, there must be a very consistent pattern to class assignment. This makes sense in the case of Yelp – elite status is determined by their Elite Council, likely with the assistance of an algorithm. I do think the model was able to nail down the algorithm quite well; the exercise certainly was a fascinating insight into the minds of the Elite Council.

Second - Since the dataset represents cumulative numbers for user activity, it’s difficult to pinpoint how many reviews or friends a user had when they became elite. A natural question here is – does becoming elite accelerate the popularity and activity of a user, therefore making him or her more likely to be classified as elite? If the data were available, I would love to do a time series analysis of the four metrics discussed in this study, looking at the specific threshold for elite/non-elite status.